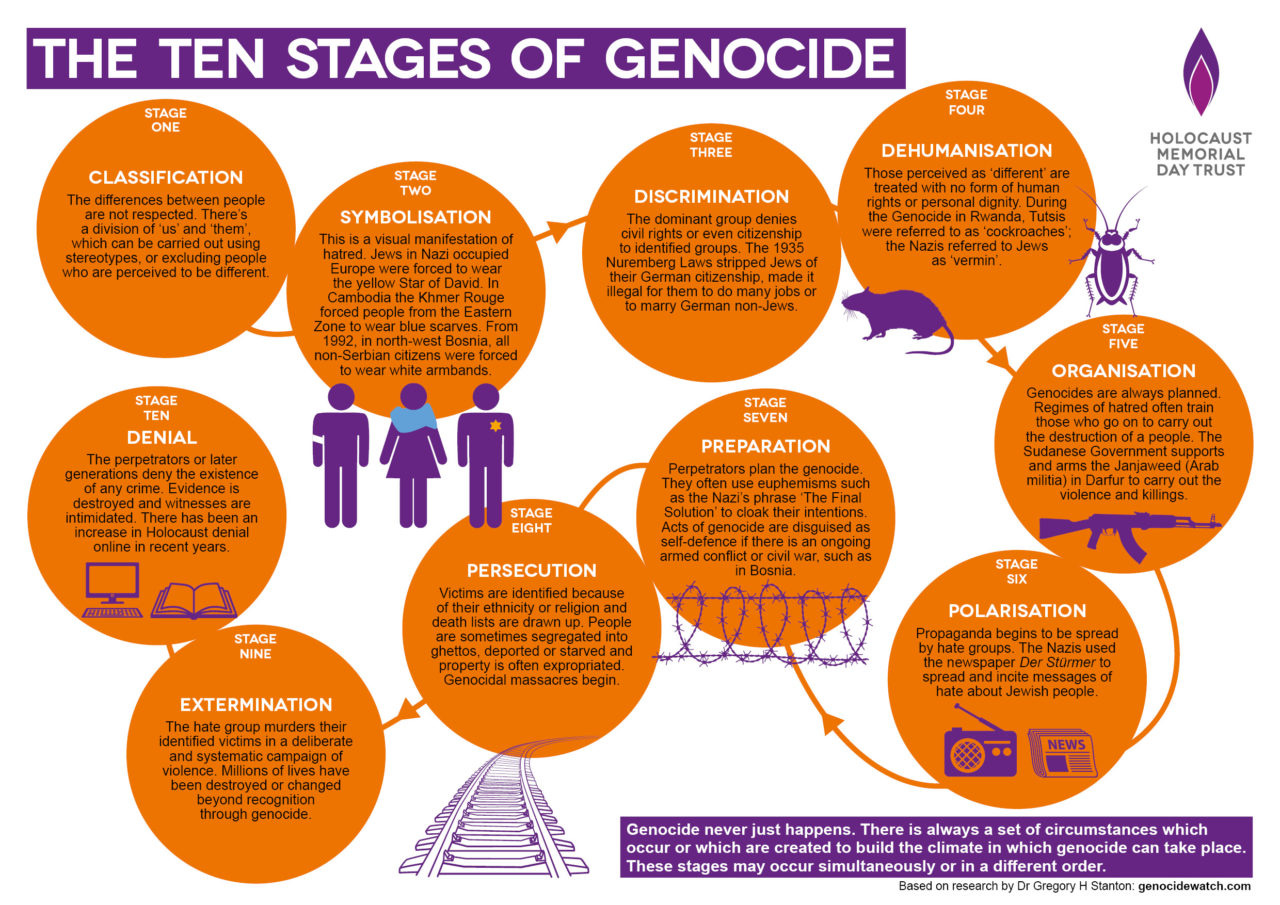

Last August we visited Kigali, the capital city of Rwanda. For obvious reasons, Kigali is the home to many genocide memorials and museums. One of those museums called the “Campaign Against Genocide” was particularly eye opening and unforgettable for me. What’s different about this museum, compared to the Kigali Genocide Memorial Museum, is that this exhibition extensively details the planning and the lead up to the execution of the genocide that took place in 1994, where almost 1 Mio people were brutally murdered. It details the political events that took place prior to the slaughters, the failures of the UN and the international community at the time, and the role the media played in inciting violence. This extremely educational exhibition is laid out in a way that it teaches you about The Ten Stages of Genocide, and shows how genocide never just happens out of nowhere, that there is always a set of circumstances which occur or which are created to build the climate in which genocide can take place.

The exhibition is housed in the old parliament building, as it was the base for the Rwandan Liberation Army, who sheltered there and engaged in mediation talks, and is therefore seen a as shrine for the liberation struggle. The exhibition itself is absolutely harrowing, and no sane person could walk through it without feeling sick to their stomach. If you’ve been to the Jewish museum in Berlin, or the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, you know that kind of sick to the stomach feeling I’m talking about. On display are photos of the perpetrators and masterminds of the genocide, absolutely disgusting humans (well, men), next to photos of hundreds of thousands of militia who kicked off the killings. There are photos of the massive piles of machetes that the so-called “financier of the genocide” Félicien Kabuga reportedly imported from abroad (there’s a documentary on Netflix about him called “World’s Most Wanted”, if you’re interested, and you’re going to get really annoyed at Switzerland if you watch it). There are transcripts of the propagandist speeches that were aired on the radio, many of which incited violence against the Tutsi. And there is ample evidence that makes up each of the ten steps that lead to genocide.

The media of genocide

A large part of the exhibition talked about the media’s role in the genocide. Journalists and experts who were covering Rwanda at the time called out the genocide months before it happened. They pointed out the dehumanizing language that was being used by the Hutu and the Rwandan media, and were not shy in highlighting the fact that it was similar language used at other times and places that helped create a climate in which terrible crimes took place (The Holocaust, for example). The Tutsi were often referred to as “cockroaches” in the media, which is coincidentally also the word that the chief of the Israeli Defence forces has used to describe Palestinians in the past. The exhibition also details how the Tutsis were often referred to as “outsiders”, and that killing them would be an “act of self defence”. “If we don’t do it to them, they will do it to us” was a quote that often headlined newspapers and radio shows at the time. What the exhibition tries to emphasize is that language matters, and history shows that language dehumanizes, incites, and leads to violence. The hate media in Rwanda – through their journalists, broadcasters and media executives – played an instrumental role in laying the groundwork for genocide, then actively participated in the extermination campaign.

“There can be no more important issue, and no more binding obligation, than the prevention of genocide.” - The United Nations Secretary General, 2004

Feeding the fear

The exhibition showed how radicals staged the practice for the tragedy to come. The “rehearsals” took place across dozens of communites around the country, the most significant between 1990 and 1993. These numurous violent attacks killed almost 2,000 Tutsis and established patterns for the genocide in 1994. Authorities tolerated and even incited these small-scale attacks, and used them as an opportunity to strengthen their position. The authorities were excellent at “feeding the fear” and used lies, exaggeration, and rumors to make the general propaganda against the Tutsi more immediate and frightening - they manufactured a real sense of danger. Some of the lies included officials telling people that Tutsi planned to exterminate the Hutu and had already killed Hutu in their region. They told them that Tutsi had killed two important military men from the region, and that Tutsi had attacked children at local schools. Authorities even went as far as staging fake assaults. So you can imagine that by April 1994 assailants were well accustomed to attacking their neighbors, and with a well trained militia like that, it was possible for government officials to play a less public part in the slaughter.

Impunity

When confronted with reports of killings between 1990 and the genocide in 1994 by foreign bodies, authorities often denied that slaughters had taken place. This worked best in cases where killings had taken place in remote and inaccessible locations. When the lies were revealed and the massacres could no longer be plausibly denied, authorities had a range of excuses ready and declared that Tutsi were being killed because they had “launched an unjustified war against Rwanda in the first place”. The Rwandan government (led by President Habyarimana at the time) were well aware how easily foreigners accepted explanations of “ancient, tribal hatreds”, and the “tribal” nature of the killings was repeatedly mentioned in accounts. So even as evidence of human rights abuses mounted, the world was reluctant to admit wrongdoing by the Rwandan government and unwilling to admit that ethnic conflict posed serious risks. In addition, Rwanda still continued to receive foreign direct aid (Rwanda was hugely dependent on foreign aid at the time) through institutions like the World Bank and the European Union. Nobody was ever convicted of any crime in connection with the massacres that took place in the three year lead up to the 1994 genocide.

The International Commission of Inquiry into Human Rights Abuse in Rwanda

Rwandan activists expected more from the donors who always spoke so highly about the importance of human rights. To focus foreign attention on the seriousness of the problem, the activists in the coalition “CLADHO” (long French name that I’m not bothered typing out here) pressed international human rights organizations to mount a joint commission to examine the human rights situation in Rwanda. Four agreed to do so: Human Rights Watch (New York), the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues (Paris), the International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development (Montreal) and the Interafrican Union of Human and Peoples’ Rights (Ouagadougou). During an inquiry in Rwanda in January 1993, the International Commission collected substantial data to show that “President Habyarimana and his immediate entourage bear heavy responsibility for these massacres (from 1990 through to 1993) and other abuses against Tutsi and members of the political opposition.”

The report, which was published by the commission in March 1993, put Rwandan human rights abuses in front of the international community. Still, international bodies “expressed concern”, but took no effective action to insist that the guilty be brought to justice or that such abuses not be repeated in the future. Governments never publicly criticized the massacres documented in the report, and many made no significant changes to their aid programs. Any changes to aid programs that were made (like the US and Canada) were linked to Rwandan fiscal mismanagement, and not human rights abuses, which significantly weakened the impact of their decisions.

The report was even presented to the United Nations Human Rights Commission, but it declined to discuss the matter in open session, reportedly because it had “too many other African nations already on its docket”. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Summary, Arbitrary and Extrajudicial Executions went on a mission to Rwanda in April 1993 and produced a report that largely confirmed the report of the International Commission. Referring to the possibility, also raised by the International Commission, that the massacres of the Tutsi might constitute genocide, the special rapporteur concluded that in his judgment the killings were genocide according to the terms of the 1948 Convention for the Suppression and Punishment of Genocide.

To prevent any further damage to his image, Habyarimana (Rwandan President) and the Prime Minister responded to the charges of the International Commission in a formal statement. In it they said that they “recognize and regret the human rights violations committed in our country.” They continued to deny that officials had taken the initiative in any of the abuses, and of course they also launched efforts to discredit the commission, referring to the four human rights organisations as “fake”. In the end the international community was willing to accept “less massacres” (as promised by the Rwandan government) and continued to accept impunity for killers in official positions. This ended up contributing to the very result the international community wished to avoid - slaughter on a catastrophic scale. Habyarimana’s supporters learned that this kind of violence would be tolerated by the international community, and it was.

The G word

One of the things that scared me the most after visiting this exhibition is the fact that the international community was not prepared to call out the signs of a genocide. Genocide is a very dicey word because as soon as it’s uttered, and a genocide is said to be occurring anywhere in the world, the international community is obliged to act. In the case of Rwanda, the international community skirted around the G word, even though all the signs were there. Failing to recognise this meant that no effective action was taken and hundreds of thousands of lives were lost. Nations were aware of the state of affairs in Rwanda and continuously termed it as an “ongoing civil war” and a “complex situation”. A “complex situation”, now where have I heard that one recently…

“The darkest places in hell are reserved for those who maintain their neutrality in times of moral crisis” - Dante Alighieri, Canto 3, Inferno

Further reading & watching:

Thank you for reading Postcards from Africa!

Don’t forget to subscribe, if you haven’t already…

Incredibly in depth for a Substack newsletter. Thank you for the background, history, context. An age old ploy by those in power to gain more: play on fears of the other. I struggle with the idea that humans have such large capacity it seems to hurt and kill others.