Reflections on South Africa

Snippets of things that grabbed my attention during our two months there

You know those snippets of information you collect when you travel to a new place? Here’s a taste of some of the unique things that grabbed my attention and stuck in my head while we were in South Africa:

Load shedding

Load shedding is a phenomenon you will only come across in South Africa. While power cuts were common in the other African countries we travelled through, in no other place were the power cuts planned on a daily basis. It’s in South Africa where electricity preceded candlelight. Long story short, there is not enough electricity to go round in South Africa, and the government are forced to ration the supply. They do this by planning power cuts and notifying the citizens via a website or app (see loadshedding.com/map/). The load mapping schedule has almost replaced the clock at this stage, with people resorting to setting their wake up alarm on their microwaves, in case they haven’t charged their phones before going to bed. You know you’re an amateur when you go to bed during load shedding, only to be woken up by all the lights coming back on after an hour of sleep. Or when you walk into a coffee shop during load shedding, only to realize that the coffee machine needs electricity to run. Happened to us too many times! But the South Africans are resilient people, and you can even find tv programs and magazines with ideas of what to cook for dinner during load shedding. It’s really no wonder that Braii-ing (Barbecuing) is such a big thing there…

Here’s quite an interesting short documentary by The Financial Times, shedding light (no pun intended) on the deep rooted issues of corruption and failures at the state-owned main electricity provider Eskom: How corruption and crime turned the lights off in South Africa.

Desmond Tutu & the Anti-Apartheid Convergence

The divestment section of the Tutu exhibition at the Apartheid Museum particularly caught my attention, and to be honest, we didn’t really know anything about it until then. If you’ve been living in a hole for the past thirty years, then it’s possible you haven’t heard of Desmond Tutu. Nobel peace prize winner Tutu, who was the archbishop of Cape Town, was primarily the voice of the oppressed during apartheid, but was also the one demanding boycott of, divestment from, and sanctions against the apartheid regime on the other.

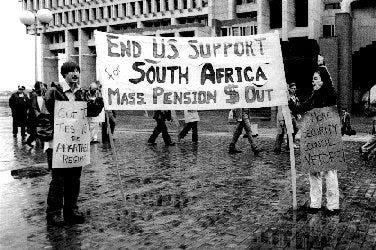

The campaign to divest from South Africa gained prominence on university campuses in the United States in the mid-1980s. Protests erupted across the country when anti-apartheid activists in the US found that Washington was unwilling to get involved in economically isolating South Africa, despite the UN having passed a non-binding resolution calling for the imposing of economic sanctions on South Africa in 1962. The activists lobbied individual business and institutional investors to end their involvement with or investments in the apartheid state as a matter of corporate social responsibility. With the help of some faith-based institutional investors, the campaign came up with principles, which, when applied to companies, directly conflicted with the mandated racial discrimination and segregation policies of apartheid-era South Africa.

The campaign then moved to lobbying individual businesses and institutional investors to adopt and comply with these principles, as well as advocating that institutional investors (particularly public pension funds) withdraw any direct investments in South-Africa based companies. Concerned stockholders of companies with South African interests even started to submit shareholder resolutions (which were routinely rejected due to management proxy votes). By 1988, 155 educational institutions had partially of fully divested from South Africa, and many US states and local governments took some form of binding economic action against companies doing business in South Africa, which also affected public pension funds. Legislative efforts were made on a federal level, which put pressure on the South African government. The college-based divestment efforts may or may not have played a role in immediately affecting the South African economy, but they did raise awareness about the problem of apartheid. After the divestment movement gained worldwide notoriety, U.S. Congress was moved to pass a series of economic sanctions against the South African government. It’s a great example that shows that boycotting, sanctions, and divestment (BDS) are powerful tools that can be used to tackle injustices. Not to mention the fact that university protests can change people’s world…

The Bromwell Street Eviction

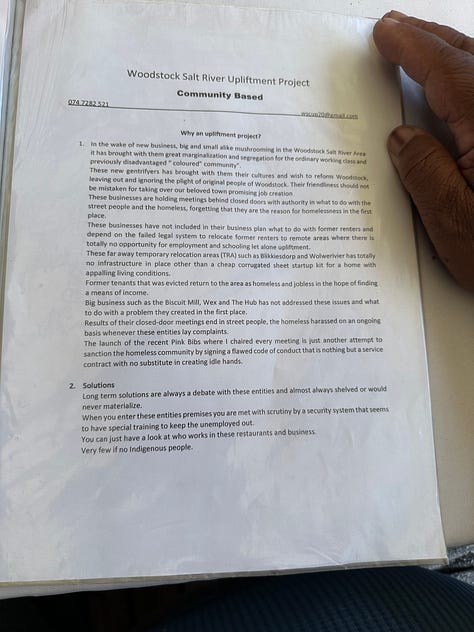

While we were visiting the (extremely gentrified) neighborhood of Woodstock in Cape Town, we met a man named Eddie Thompson and ended up having a two hour eye-opening conversation with him. When you arrive in Woodstock you first notice the recent development in the area, like the renovation of old buildings and factories, and the numerous coffee houses and boutiques. It’s very obvious that investors have spent a lot of money here to develop, but that depends on how you define development… Historically Woodstock is a black neighborhood, but with the inflow of money in recent years, the blacks are being forcibly pushed out (sometimes to settlements over 50km away!). Eddie Thompson is a local community activist, born and bred in Woodstock. Eddie is extremely concerned by the new businesses “mushrooming” in the Woodstock area, which in his words has brought with them “great marginalization and segregation for the ordinary working class and previously disadvantaged “colored” community”. These gentrifiers have brought with them their cultures and wish to reform Woodstock into a place that caters solely for tourists and upper class citizens, ignoring the plight of the indigenous of Woodstock, and filling them with empty promises of job creation.

To raise awareness of the issue, Eddie founded the “Woodstock Salt River Upliftment Project”, a movement that aims to be part of the development conversations, which he says take place behind closed doors and do not involve the affected people. His biggest worry is the relocation of the former renters, the homeless, and the jobless. These people are often relocated to remote areas with no opportunity for employment and schooling, let alone upliftment. There is little infrastructure in place for them, and the resettlement scheme provides them with cheap corrugated metal sheets as a “start up kit for a home” - these people end up in appalling living conditions. All Eddie wants is that the business plans of these developers include a better solution for the indigenous of Woodstock, so that they can also benefit from the opportunities, and at the very least that the investors and developers are transparent in their communications and reporting. “If you make 50 people homeless, then you better publish that metric in your annual report!”. Ironically enough, not a day passes where Eddie doesn’t get an offer from an investor for his property on Albert Road in Woodstock…

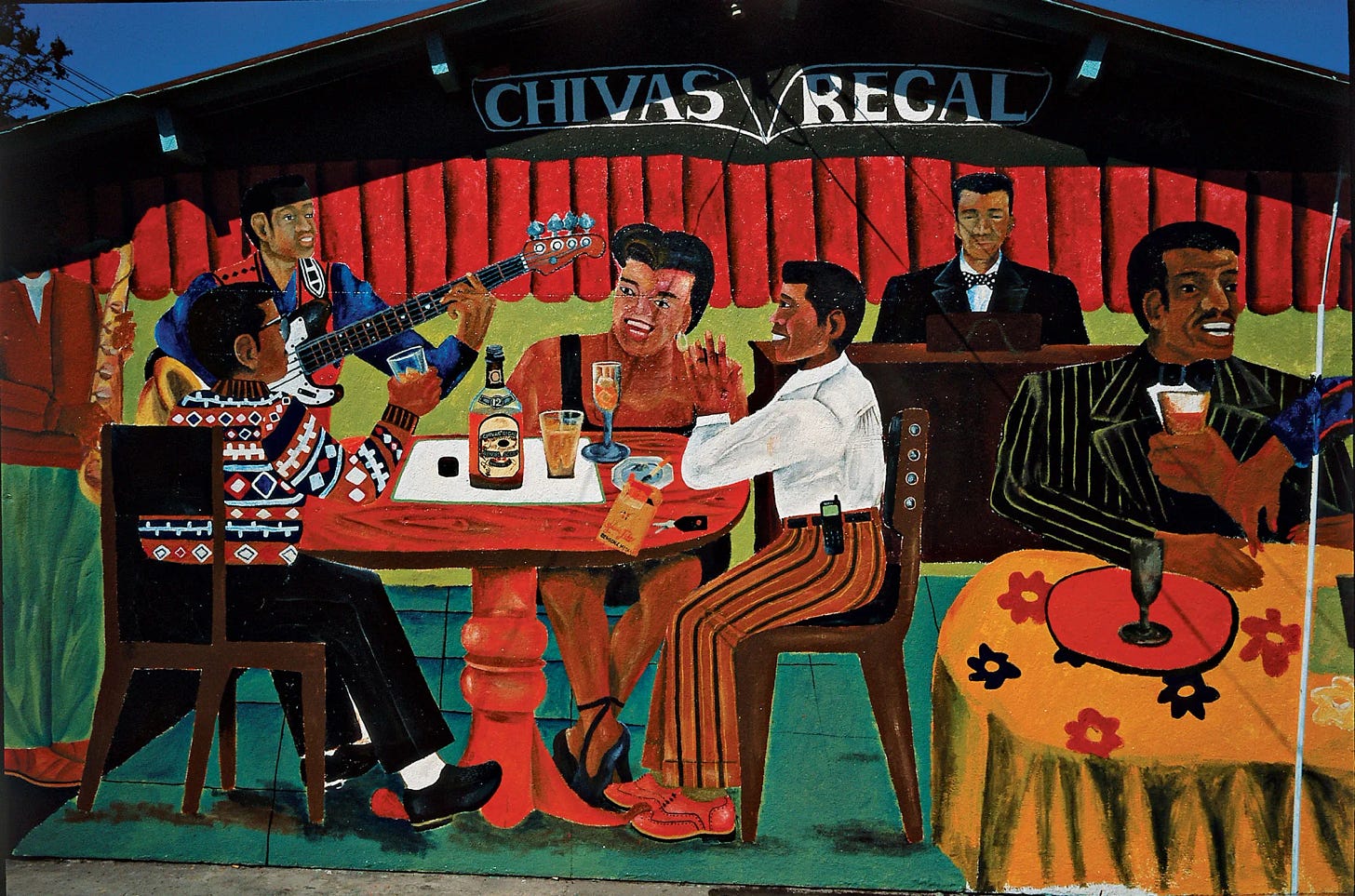

The Shibeen Queens

When I heard the word “shibeen” mentioned, my ears naturally pricked up. Shibeen comes from the Irish word “síbín”, and is an unlicensed establishment or private house selling alcohol. In South Africa, it’s a speakeasy. Speakeasies popped up all over South Africa in the 1800’s when it was illegal for a black person to sell alcohol. But the real legends are the Shibeen Queens, who were the savvy business women who ran them from their own homes. The Shibeen Queens were also the ones brewing the beer, using generations-old recipes and a mixture of maize, malt, sorghum, yeast, and water.

Particularly after apartheid legislation was enforced in 1948, the Shibeens became safe havens for those seeking to express their thoughts freely. They also became a breeding ground for self expression and many trailblazing African jazz (kwela) musicians emerged from their shadows. This subculture wouldn’t have existed without the Shibeen Queens, who despite the most difficult of conditions managed to set up thriving businesses and provide for their families. By the 1960’s there were reportedly more than 10,000 Shibeens in Soweto alone. Just like all good things, you see a resurgence of these cultural relics in honor of the hardships of the past, although these ones are manufactured and repackaged with licenses. Check out this photographic work featuring some of the Shibeen Queens of South Africa.

Palestinian Solidarity

Thank you for reading Postcards from Africa.

Don’t forget to subscribe, if you haven’t already…