If you know us well, you probably know that we both tend to buy secondhand clothes, as opposed to always opting for new clothes. In fact, we really enjoy shopping for pre-loved clothes, finding those gems among the rags, and were pleasantly surprised to see the quality of secondhand clothes for sale in Uganda. Used and secondhand clothes exported to East Africa are known locally as “Mitumba”, a Kiswahili word meaning bale or bundle, as it is typically sold to retailers in bales. In the past, used clothes were called “Kafa Ulaya”, meaning “clothes from someone who died in Europe”. You can’t help notice the mix of styles, eras, and cultures that the secondhand clothes bring to the streets of Kampala and other Ugandan cities. You might see a traditional patterned skirt paired with a retro band t-shirt, or even a Lakers jersey. Or a Boda-Boda driver wearing a fleece that was once part of an American fast food chain’s uniform. One day we saw a farmer wearing a t-shirt with “this man needs a beer” written on the front of it. And the best was when we saw a young boy wearing an Offaly jersey. At a first glance, it’s great to see an entire nation proudly wearing and embracing secondhand clothes, even if it is more out of necessity rather than choice. But there is also an ugly side to it, and that ugly side originates in the fast-fashion system of the Global North.

When the English colonized Uganda they put massive emphasis on cotton growing as a cash crop, and parts of Uganda were made relatively prosperous due to cotton. In fact, Uganda used to be one of the highest producers of cotton in Sub-Saharan Africa and had a thriving textile industry. The downfall of the industry is said to be due to cotton markets becoming globalized, Uganda’s lack of buying power, and to Idi Amin expelling Asian people (mostly Indians) from Uganda in the 1970s. Asians, who inherited the managerial positions from the British, were the ones running the textile factories. A lot of the know-how left with them and nothing but the infrastructure remained. Secondhand clothing coming from the Global North is also a factor in the near-collapse of the garment industries in sub-Saharan Africa. Clothes from the West were so cheap in comparison, that it was impossible for local textile factories and tailors to compete. In other words, we are also part of the problem.

The result is a country that relies almost totally on the import of secondhand clothing to clothe its people, and 95% of the high-quality cotton that is still produced today, is exported. The US is the top supplier of secondhand clothing to Uganda. In 2015, the Ugandan government proposed a ban on the importation of secondhand clothes in an effort to nurture the local resources and revive the cotton industry. Uganda wanted to wean itself off the used clothing trade. However, the US pressured Uganda into not moving ahead with the ban and introduced an “African Growth Opportunity Act”, which gave preferential trade treatment to Ugandan products entering the US market. The act, which means that the US can continue sending their textile waste (often disguised as secondhand clothing) and avoid the responsibility and costs of dealing with disposable clothes, expires in 2025.

Fast forward to late August 2023, and Museveni (the Ugandan president) pledges yet again to ban used clothing imports - the controversial secondhand clothing trade is part of the political discussion once more. For communities across Uganda, the announcement is a slap in the face. While cotton is considered one of the key commodities for generating household incomes, creation of employment, and alleviating poverty in Uganda, an outright and immediate ban on secondhand clothing imports shouldn’t be the first step towards achieving this.

Secondhand fashion supports many livelihoods and communities across Uganda - importers, market vendors, up cycles, fashion designers, artists, and waste managers. According to the Uganda Dealers in Used Clothing and Shoes Association, there are more than 4 million Ugandans directly and indirectly active in the used-clothing and textiles supply chain. Secondhand textiles are also a valuable source of tax revenue for the country. Major suppliers are based in China, US, Canada, UK, Turkey, Australia, and the UAE. Owino market in Kampala is the biggest market in Uganda. It accommodates more than 50,000 market vendors and traders, most of whom are women, and is famous for secondhand clothes. What happens to those vendors when a ban is enforced? Will they be compensated or given jobs? If the government does what it promises to do and replicates the textile factories of Asia and offers thousands of people employment, will the employers ensure that humans are not exploited? And how will Ugandans afford to dress themselves going forward?

The other side of the coin is the fact that Africa has been and still is treated as the “waste disposal system” by the developed world. As well as damaging the African textile industry, the used clothing trade has also damaged and polluted the environment, as a lot of these donated clothes are of such poor quality that they go straight to the dump. According to available data, only about half of the exported used clothes can still be reused as clothing. It’s a disgusting example of the ignorance of the developed and over-consuming countries of the Global North, thinking that their shitty clothes are fit for donating. Uganda weaning themselves off the used rag trade is one way of tackling this, but it’s also worth questioning why we think it’s ok that the dregs not fit for charity shops in the West are dumped in places like Uganda, and what impact this has had on their economy, environment, and culture.

While it might be necessary for Uganda to curb the secondhand clothing trade in order to grow the local textile industry, banning everything at once takes the power away from the people. As destructive and controversial as the current system is, it works, and a lot of people depend on it. One could argue that the root of the problem lies with us, the Global North. We have found a way to get rid of our textile waste and we force the Global South to deal with the consequences of our fast fashion, even though they have no infrastructure to do so. Perhaps we should think about calming down and stop consuming so much… We should maybe also start to look into where we are donating our old clothes, and who’s running the charities. We need to remember that clothing does not begin and end with our shopping experiences, our clothes are part of a much larger cycle.

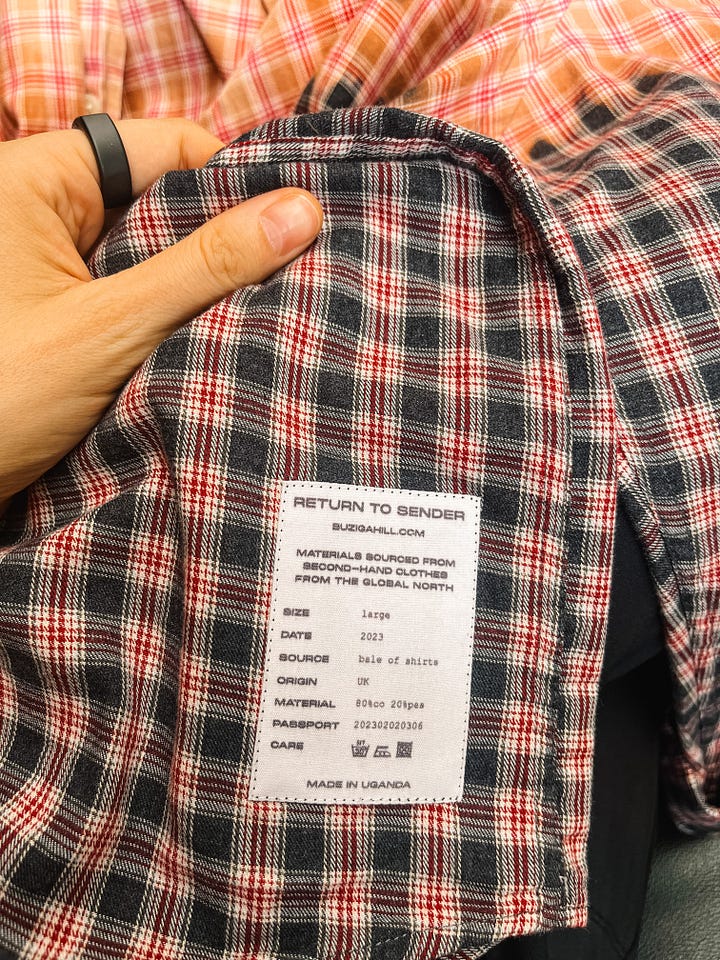

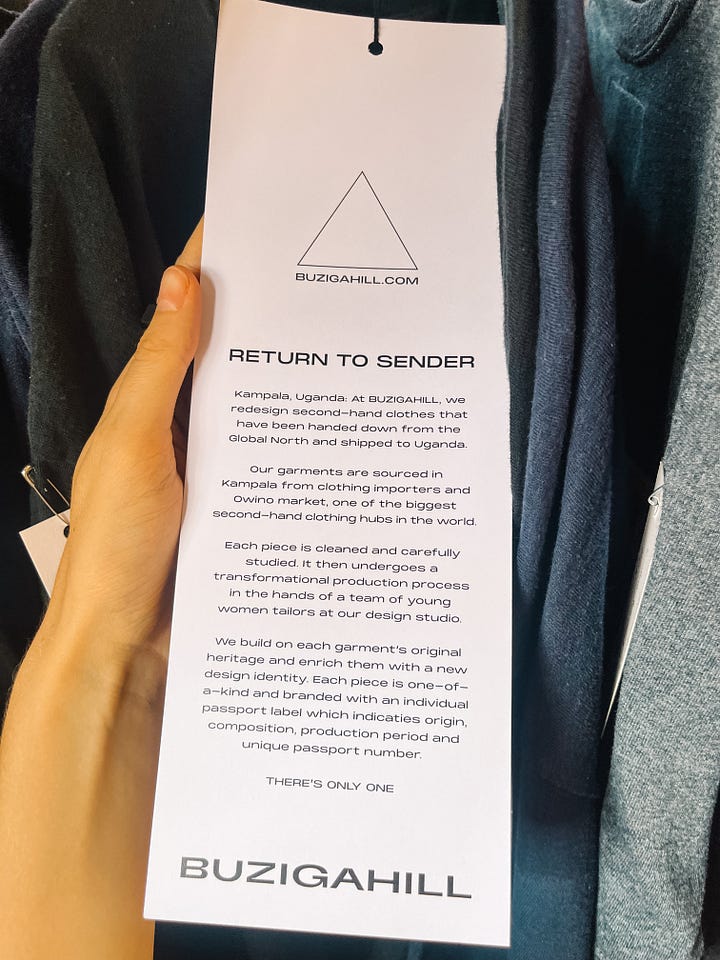

If you are interested to read more about what is happening in Uganda on the topic of fast fashion and the secondhand clothing trade, you can check out the podcast series “Vintage or Violence”. BUZIGAHILL is also worth checking out. It’s a clothing brand based in Kampala, whose project “RETURN TO SENDER” redesigns secondhand clothes and redistributes them to the Global North, where they were originally discarded before being shipped to Uganda. The project is a direct response to the impacts of secondhand clothing on Uganda’s textile industry, and is part of a national textile and clothing movement. We checked out the BUZIGAHILL brand when we visited the Aiduke concept store at 32° East Arts Trust Centre in Kampala, and even purchased some of the one-of-a-kind and super cool RETURN TO SENDER items. The Centre houses “Aiduke”, which is a non-profit that collaborates with small-scale textile producers and designers, aiming to enhance overall textile and garment production in Uganda.

Sources & links:

Cotton and its by-products in Uganda

The impact of secondhand clothes and shoes in East Africa

How the US and Rwanda have fallen out over secondhand clothes